The Spa Ponds Heritage Project was established to investigate, celebrate and protect the heritage of Spa Ponds Nature Reserve in Forest Town, Mansfield, and is supported by a Heritage Lottery Fund Sharing Heritage grant of £8,500.

On Friday 7th July 2017 James Wright delivered a Mediaeval Landscape Day School for the Spa Ponds Heritage Project. Shlomo and Josh’s account of the day is below:

The Day School was entitled: ‘Kings, Knights and Knaves of Clipstone – A Day School Exploring The Mediaeval Landscape of Sherwood’, which was a fitting title, as author and archaeologist James Wright provided participants with a four-in-one treat in the form of a comprehensive Day School that featured:

- A seminar exploring the definition of a castle;

- A lecture focusing on elite landscapes;

- An engaging seminar about Mediaeval hunting; and

- A lecture that looked at the theme of revolt against authority in the 14th and 17th centuries at Clipstone.

Seminar – What is a castle?

Spa Ponds sits within, or alongside, the Mediaeval context of Clipstone Peel, a fenced enclosure on the edge of Clipstone Park. Our knowledge of the peel site from Mediaeval sources and modern analysis of the political situation at the time indicate that the peel was intended, at least in part, to provide a secure location for the king to reside during a time of political strife (in particular King Edward II’s ongoing feud with Thomas, Earl of Lancaster). Because of this, Clipstone Peel shared many features and purposes in common with medieval castles.

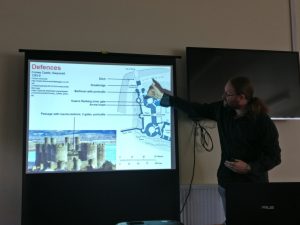

We began the day by identifying some of the castles that we had visited, and James impressed us all with his intimate knowledge of so very many castles. This was the prefect start to our consideration of the basic but tricky question: “What, pray tell, is a castle”?

For example, the building at Bolsover has been rebuilt – is it still a castle? And what of the construction at Disneyland – although it is clearly an attempt to reflect an archetypal castle – does it meet the definition of a castle? What qualities need to be present for a structure to constitute a ‘castle’?

James noted that castles are built for not by royalty and others. We discussed who commissioned castles to be built and we generated a list that included: kings and queens; other royalty (such as dukes, barons, gentry, and other aristocrats, e.g. in Wales); and other landowners, including magnates (e.g. Henry Percy), statesmen (e.g. Ralph Cromwell); knights; The Church and associated religious orders and bishops, e.g. fortified structures at priories, and Newark Castle (Alexander the Magnificent was a bishop). Vikings built fortifications for their armies, crusaders built castles, and some castles built for wealthy merchants, e.g. Lawrence de Ludlow.

We went on to consider the sorts of buildings and rooms and architectural features found in castles, and how many of these are reflected in contemporary buildings to this day. All these considerations helped frame the tricky question: Are castles built primarily for military purposes or to provide a residence, or both? We identified plenty of non-military uses of castles, thus ruling out the notion that castles are (or were) exclusively built for military purposes, even if they inevitably reflect “an architecture of power”.

Lecture – Elite Landscapes: Beyond the Castle Gate

James’ lecture on elite landscapes drew our attention to the deliberate relationship between windows, nearby gardens, and the larger landscape context (park land) that can be seen further afield. James pointed to the religious influences, whilst noting that castles were sometimes but not always located near churches.

We learned about the classic motte-and-bailey castle design, with James explaining that a motte is a mound of earth and a bailey is an enclosure. Castles are located at high points in the landscape, e.g. Bothamsall on Castle Hill on a former Saxon enclosure with the motte in the middle.

The building of a castle sometimes required the clearing of woodland to create lawns (including deer lawns). The landscapes within which castles are located include both functional and symbolic elements. Good landscape management was associated with good management of the kingdom as a whole.

The royal hunting land of Clipstone Park was thought to have been a key part of the visual and symbolic landscape of King John’s Palace, known as the King’s Houses, with the ‘wilderness’ of the forest contrasting with the more managed gardens of the palace complex.

Seminar – An examination of Mediaeval hunting with reference to Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

James’ creative approach to teaching made use of poetry, in particular selected passages from Simon Armitage’s contemporary translation of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, to help us appreciate what went on at deer parks, such as the one at Clipstone Park. Again the symbolism was apparent, with lording it over the deer and lording it over the landscape representative of the ruler’s power – hence the association between hunting and the aristocracy.

Participants were split into several small groups to facilitate our close consideration of James’ carefully selected excerpts from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. This process introduced us to a series of fairly gruesome words and images, such as “numbles” (entrails), “gralloching” (disembowelling), and other terms associated with the ritual butchering of deer killed in the hunt.

It became abundantly clear that the many rituals and customs associated with Mediaeval hunting served to reinforce the social order. For example, social status determined which cuts of meat were given to whom, with the hunting dogs shown preference over and above the local villagers. There was also evidence of superstition, such as the reference to paying a ‘fee for the crows’.

Whilst aristocratic hunting was not a very practical means of gathering food, in addition to its social function it did also serve the additional purpose of helping to train horses and men to be better prepared for warfare. The hunting techniques employed required planning, coordination between participants, and the ability to function on difficult and noisy terrain.

Lecture – Royalty, Rebellion and Revolution in Sherwood Forest

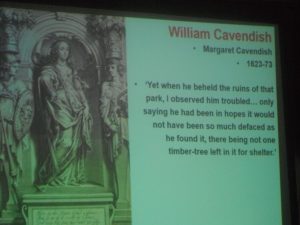

James’ lecture entitled ‘Royalty, Rebellion and Revolution in Sherwood Forest’ looked at the theme of revolt against authority in the 14th and 17th centuries at Clipstone. The 14th century focus was on Edward II, the peel and Robert de Clipstone. The 17th century focus was on revolution, recusants and witches. A recusant is a person who refused to attend services of the Church of England.

James noted that the first written record of the Kings Houses at Clipstone being described in as “King Johns Palace” was Chapman’s map of Nottinghamshire (1774).

Edward II had a great love of hunting, and timed his visits to Clipstone to correspond with deer hunting seasons. He was not universally respected, as he was seen as weak. Edward II lost the Battle of Bannockburn to the Scots in June 1314, and his power was diminished by this defeat. This added to his problems with Thomas, Earl of Lancaster.

Edward II’s ban on tournaments was described as another sign of his weakness, as Edward II needed to maintain control during his turbulent reign. This adds to the notion that Edward II had the peel (fortified structure) at Clipstone built as both a defence (against Thomas, Earl of Lancaster) and to provide Edward II with a place to hide if need be. There is some evidence that Edward II stayed at the Peel rather than the Kings Houses in order to be safer from Thomas, Earl of Lancaster.

Edward II may have fled the country, despite reports that he was murdered in Berkeley Castle. Whatever the case, it is universally accepted that Edward II was forced to relinquish his crown in January 1327, when his fourteen-year-old son, Edward III, became king (at least in name). It is thought that the true power during the start of Edward III’s reign was his mother Isabella and her lover Roger Mortimer.

The turbulence of these times may help explain the boldness of the local people who rose up to petition the King to return to them the land rights that were taken away when the Peel was erected and lands taken for the King for the Peel and adjacent farmland. Robert de Clipston is recorded as having been one of the original petitioners in relation to the peel was also the “keeper of the manor and park of Clipston” in 1328, when the Peel was dismantled early in the reign of Edward III. Some of the disputed land might have included the area we now know as Spa Ponds.

A full account of the petitioning and subsequent throwing down of the Peel is included within Jame Wright’s “A Palace For Our Kings“.

In the 17th Century there was a spike in the number of recorded recusants (i.e. those not attending church and instead submitting to the authority of the Pope) and an apparent increase in the number of ritual protection marks, reflecting the social tensions of the times.

There is the possibility that Beeston Lodge was named after the family of Thomas Beeston Senior who was a Nottinghamshire yeoman and 17th century recusant.

MORE ABOUT JAMES WRIGHT

James Wright FSA is an archaeologist and historian who is currently a doctoral researcher at the University of Nottingham With over twenty years of professional experience, he has published two books and a string of popular and academic articles concentrating on the British Mediaeval and Early Modern periods. He is a very proficient public speaker and has spoken to a wide variety of organisations including a large number of local history societies, LAMAS, Thoroton Society, WEA, Thames Discovery Programme, Nottinghamshire Local History Association, U3A, Lowdham Book Festival and the Fortean Society. He has also been invited to speak by the University of Nottingham, Gresham College, Shakespeare, Museum of London, Historic Royal Palaces and the National Trust. He presents in a clear and conversational style (without notes or script) and readily uses illustrative slides throughout his lectures. The talks are adaptable and can be presented to novice, mid-level or expert audiences.

For yet more, see: http://nlha.org.uk/news/james-wright/ and http://www.triskelepublishing.com/jameswright/